by Anonymous, submitted 28 August 2021

‘What are you trying to get out of this?’

The words of my GP echo through my head. It has taken me 6 months of battling with my surgery to be referred for an ADHD assessment, and I’m finally on the cusp.

‘The symptoms you have are also symptoms of depression and anxiety, so how do you know you’re not just experiencing those?’

Gee, I don’t know… maybe that’s why I want an assessment.

‘How will you feel if you don’t get diagnosed? I’m just worried you’re pinning all your hopes on this’.

Trust me, after what I have been through, I can handle it.

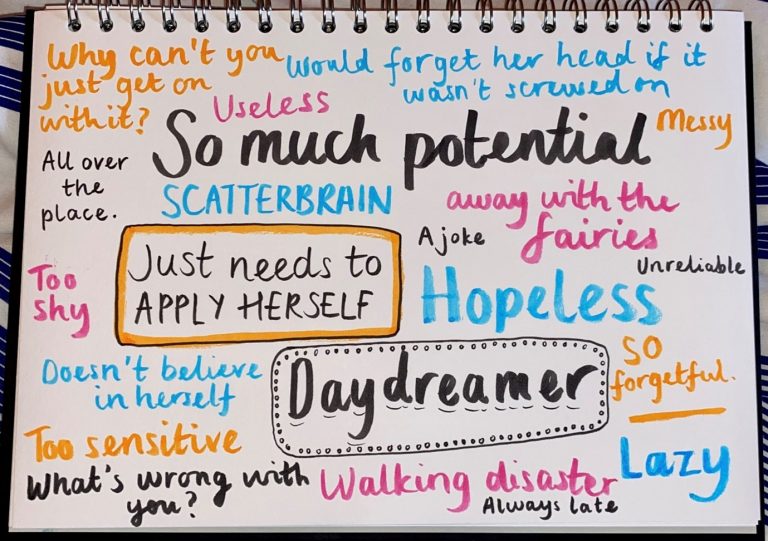

My journey to diagnosis started one year ago, when my oldest and best friend turned to me and explained that she had recently done a course about adult ADHD. There were women with similar stories to mine, who had battled with depression and anxiety for as long as they could remember, had low self-esteem, and felt that nothing they did to improve their mental health had any lasting impact. These women were struggling to focus, chronically overwhelmed and burnt-out, and felt that no matter what they did, they couldn’t keep up with the demands of day-to-day life. After a lifetime of unnecessary struggle, they were diagnosed with ADHD.

ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that has 3 sub-types: Inattentive, Hyperactive and Combined (which has elements of both). People with inattentive ADHD have trouble holding their attention, may be forgetful, struggle to get organised and find themselves easily distracted. Those with Hyperactive ADHD might feel as though they have racing thoughts, are always ‘on the go’, struggle to stay sitting down, constantly fidget and interrupt conversations. (DSM-5)

These symptoms, which all form part of the ‘tick box’ process when being referred/assessed, are just the tip of the iceberg. There is an emotional impact that runs much deeper, particularly for women and girls.

When most people hear ‘ADHD’ they have a very specific image in mind: a naughty schoolboy who can’t sit still. The default assumption seems to be that to have ADHD you must be hyperactive, loud and disruptive. You must be bouncing off the walls. People want to see it to believe it.

In actual fact, many people, especially those with inattentive ADHD, are extremely shy. It is clear that there is a serious lack of understanding of the condition, and how it may present. ADHD is chronically underdiagnosed in girls – they weren’t included in research until 1997, and up until then it was believed that boys were 9 times more likely to have it. Girls tend to present with fewer disruptive behaviours, which can be more difficult to recognise. This along with gender expectations, could lead to a gender bias in ADHD in terms of identifying patients and initiating referrals (Young et al, 2013).

Studies show girls are much more likely to internalise their struggles and mask symptoms. And internalise, I did. Cripplingly so…

The forgetfulness, the time blindness, the issues focusing, I blamed myself for all of it. The frustration I felt with myself had such an impact on my self-esteem that my confidence was non-existent. As I felt others around me become frustrated with my behaviours, I internalised this and the impact on my self-image was devastating.

Imagine the emotional toll of not only feeling that there is something wrong with you but feeling like you are the only one. The rates of co-morbidity between ADHD and mental illnesses are shocking. Research has found that 80% of people with ADHD will have at least one other psychiatric condition in their lifetime (Sobanski et al, 2007), 30% of children with ADHD have mood disorder such as depression (CHADD, 2017) and up to half of girls with ADHD may self-harm (Hinshaw, et al 2012)

Many researchers argue that Deficient Emotional Self-Regulation, or DESR, should be included in the diagnostic criteria for ADHD. Emotional dysregulation is included in current Neurophysiological theories of ADHD (Nigg & Casey, 2005; Castellanos et al, 2006; Sagvolden, et al), suggesting that mood and anxiety disorders could actually be considered part of the condition rather than existing alongside it. If this is the case, why is it missing from the DSM diagnostic criteria? More understanding of this could lead to more diagnoses and therefore more early intervention.

I was first treated for depression when I was 16; after leaving the structure of school behind and heading to college, my struggles became harder to mask. I felt completely hopeless. I was prescribed antidepressants and sent on my way.

This would form the pattern for my late teens and early twenties. No matter how hard I tried, I always ended up back in that place. It was, and still is, exhausting.

My last burnout in October last year was a turning point. Taking into consideration what my best friend had said, I decided to ask my GP if I could be referred for an ADHD assessment. I was told that the closest place I could have one was Sheffield and the waiting list was three years.

It was only through my own research that I discovered Psychiatry UK and the ‘Right to Choose’ scheme. Through this pathway your GP can refer you to an external clinic, but the assessment is still funded by the NHS.

Two weeks ago, at 25 years old, I sat in front of a psychiatrist and was diagnosed with Combined ADHD.

Nothing can prepare you for the mix of emotions a diagnosis brings.

I feel relieved. I now understand that my brain is structured differently and know myself better. I can try to release some of the shame I have been carrying for all these years. There’s nothing wrong with me, I’m just a neurodivergent person living in a world built for neurotypical brains.

I feel hopeful. Hopeful that I will be able to have a better quality of life and improved mental health now that I have the correct diagnosis.

I feel angry. Why aren’t we better at understanding this? How many people are walking around without a diagnosis, carrying layers of shame and feeling that there is something wrong with them? Why do medical professionals seem to have little understanding of the emotional impact of ADHD?

How many people are no longer here with us, because their mental health struggles were too much to bear? Over the last 10 years I have been in some really dark and lonely places that I thought I would never get out of. Many times I felt like there was no point in continuing, that life would always be too much for me. I’m angry for the young girl who experienced that when it might have been prevented. I’m angry that it might have been different if I was born male.

I feel exhausted. The journey to diagnosis has been a lonely one, with very little understanding or validation from those around me. I’m tired of advocating for myself. I’m tired of not being able to tell anyone about it without having to educate them.

I feel a deep sense of grief. A grief for what could’ve been, the things I could’ve achieved, the person I might have been. A grief for those in the same position who didn’t make it.

I feel heartbroken for the little girl who never thought she was good enough.

But most of all, I’m proud of the woman I am today. I love my brain and I wouldn’t change it for the world. I’m creative, empathetic, imaginative, passionate, and fun. I wouldn’t change my experience because it’s made me who I am today. My pain gives me purpose. I don’t know what the future holds but I know that I’m going into this new chapter of my life excited and stronger than ever before.

References

Castellanos, X., Sonuga-Barke, E., Milham, M., & Tannock, R. (2006). Characterizing cognition in ADHD: Beyond executive dysfunction. Trends in Cognitive Science, 10, 117-123.

CHADD. The National Resource on ADHD. Depression. Available at: http:// www.chadd.org/Understanding-ADHD/About-ADHD/Coexisting-Conditions/Depression.aspx . Last accessed October 2017.

Hinshaw, S. P et al (2012): Prospective Follow-up of Girls with Attention-deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder into Early Adulthood: Continuing Impairment Includes Elevated Risk for Suicide Attempts and Self-Injury. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012; 80(6): 1041-1051.

Nigg, J. T., & Casey, B. (2005). An integrative theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on the cognitive and affective neurosciences. Development and Psychology, 17, 785-806.

Sagvolden, T., Johansen, E. B., Aase, H., & Russell, V. A. (2005). A dynamic developmental theory of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) predominantly hyperactive-impulsive and combined subtypes. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 28, 397-408

Sobanski, E., Brüggemann, D., Alm, B. et al (2007): Psychiatric comorbidity and functional impairment in a clinically referred sample of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosc 257, 371–377 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-007-0712-8

Young, S, Fitzgerald, M & Postma, M.J (2013) ADHD: making the invisible, visible. Available at: http://www.russellbarkley.org/factsheets/ADHD_MakingTheInvisibleVisible.pdf Last accessed October 2017.

Will you be interested in sharing your story with us?

We have been raising awareness since 30 May 2020 for un/diagnosed ADHD in Women.

By doing this, we are not only empowering women, but also supporting women by sharing our lived experiences.

Many women suspect that they have ADHD, or know that they show symptoms or have been diagnosed.

Our website is a platform to share our stories and with your help, by providing your story, will offer encouragement, hope and a better understanding about how living with ADHD actually feels.

We respect your privacy and will either upload your story anonymously or use your name with your permission.

How to share your story with us? Click here